PROGRAM

Components

Linguistics

Word Choice. To promote generalization to core content classes, words chosen for the LGS lessons consist of, as much as possible, words SWRD will encounter in science, social studies, and history in their classes. (34 words)

The Strategies. The LGS component explicitly teaches (a) phonetics (b) phonology; and (c) English orthography: skills shown to be essential for the learning of the English language [1]. It uses a structured and explicit written symbol system that combines visual and orthographic identification of letter and letter cluster sounds. LGS’s core cognitive strategy, Word Building (WB), is an adaption of segmenting and telescoping [2]. WB creates a combined auditory-orthographic activity by using a ‘Procedural Facilitator (PF)’ (a systematic cognitive strategy that structures specific instructional activities) [3]. Use of the PF and the ‘written signaling system’, on all LGS Instructional Sheets helps cue and anchor attention to individual letters and letter cluster sounds within words [4]. (113 words)

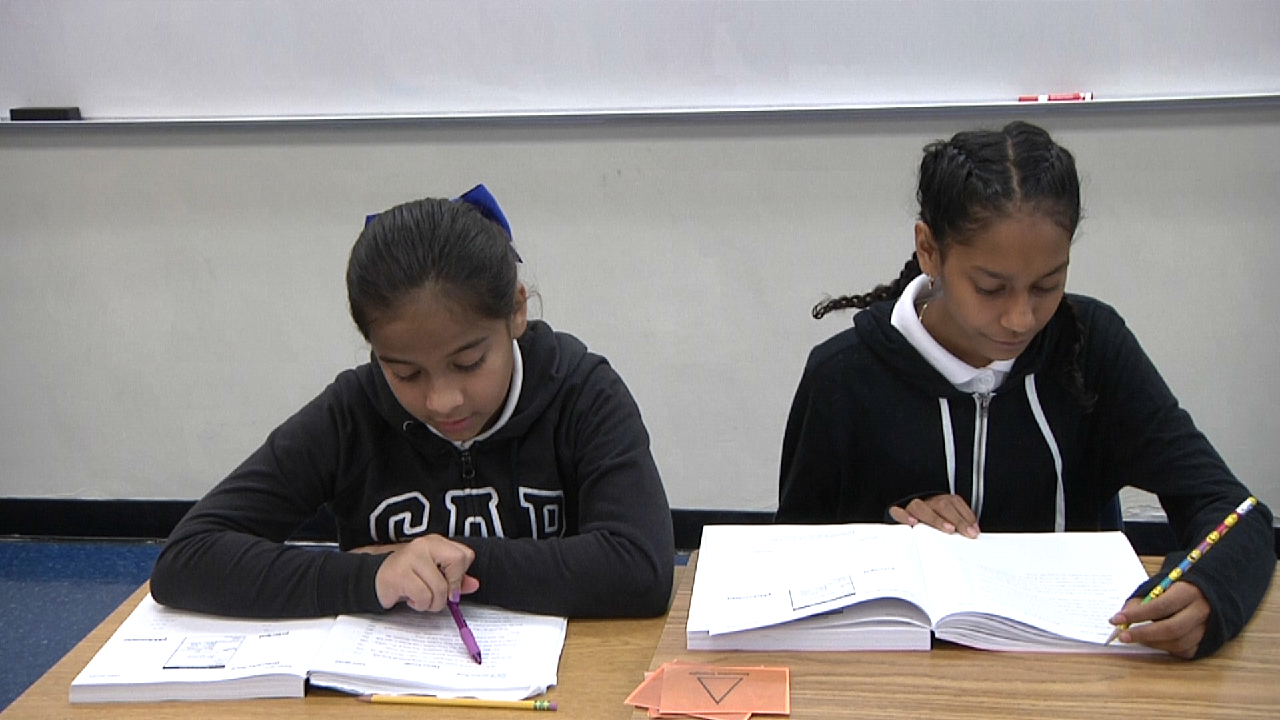

In Practice. LGS skills are introduced through explicit teacher-directed lessons using modeling and scaffolding with class-wide peer-tutoring and independent learning strategies. Each Instructional Sheet begins with a ‘Teacher Directed’ section where the teacher (as the Coach) models use of the PF while students (as the Learners) respond orally and orthographically. After the Teacher Directed portion, reciprocal peer-tutoring student pairs use the PF to continue working on the Instructional Sheet. Student Coaches are provided with Coaches’ answer sheets which support them in their roles as Coaches. Teachers circulate and provide immediate feedback to pairs during peer-tutoring. After student pairs finish the Instructional Sheet, teachers lead whole-class review through class choral reading of the words in list form. Following choral reading, students independently complete a ‘Practice Sheet’ with teachers providing immediate feedback. Lastly, students have a ‘Homework Sheet’ for more independent practice. (139 words)

[1] (Moats, 2001)

[2] (Carnine, Silbert, Kame’enui & Tarver, 2004)

[3] (Baker, Gersten, & Scanlon, 2002)

[4] (Adams, Treiman, & Pressley, 1998; Calhoon, 2005; Calhoon et al., 2010; Calhoon & Petscher, 2013; Ehri, 1991; Share & Stanovich, 1995)

Comprehension Strategies (PCS)

Passage Choice. To promote generalization of reading skills to core classes (social studies, science, language arts, etc.) and to accommodate the low reading level of SWRDs, the reading material for PCS consists of leveled texts for social studies, science, language arts, ranging in reading grade level from 1.5-8.0.

The Strategies. Based in part on the Peer-Assisted Learning Strategies program [5], the activities/strategies taught in this component are supported by research that demonstrates metacognitive strategies are an effective method for teaching comprehension instruction. PCS incorporates three essential reading comprehension activities: Echo Reading [6], Paragraph Shrinking [7] (similar to summarization) and Prediction Relay [8]. Similar to the LGS component, PCS uses reciprocal peer-tutoring [9].

In Practice. Every PCS session begins with Echo Reading, to improve student’s reading accuracy and rate, followed by a retelling of the sequence of events in the text just read. Students then flow into Paragraph Summarizing, to develop comprehension through summarization and main idea identification [10]. Lastly, Prediction Relay asks students to make prediction about what might happen next in the text before reading half a page of text to confirm or disconfirm predictions.

[5] (Fuchs, Fuchs, & Burish, 2000)

[6] (Simmons, Fuchs, Fuchs, Mathis, & Pate, 1990)

[7] (Baumann, 1984; Doctorow, Wittrock, & Marks, 1978)

[8] (Palinscar & Brown, 1984)

[9] (NRP; 2000)

[10] (Fuchs, Fuchs, Mathes, & Simmons, 1997)

Fluency

Timed Passage Choice. In order for fluency skills to generalize to core content classes, leveled texts for social studies, science, and language arts, ranging from 1.5 to 7.2 reading grade level, are used for fluency passages [16].

The Strategies. Research has shown that repeated readings of a passage helps in the development of a large inventory of quickly identifiable words [17]. It also facilitates reading fluency by increasing reading rate and improving comprehension [18]

In Practice. The repeated reading technique [19] is used for FL instruction. This technique has each student read a passage for 1 minute, then set a goal to increase the number of words read correctly during a 2nd 1 minute reading of the same passage.

[16] (Housel, 2007).

[17] (Carnine, Silbert, & Kameenui, 1997; Dowhower, 1994)

[18] (Samuels, 1985).

[19] (Stahl, Heubach, and Crammond (1997)

Working With Words (Spelling)

Spelling Choice. Knowledge of spelling is strongly related to word identification measures [11]. WWW spelling activities have shown, on average, to significantly increase middle school SWRDs spelling [12].

The Strategies. Effective spelling instruction should contain elements addressing word structure (i.e., Greek and Latin word elements), letter pattern, sound, and meaning [13]. While general reading and writing activities help students develop spelling skills through implicit modes, students benefit greatly from explicit, systematic spelling instruction [14]. AMP-IT-UP strategically combines implicit spelling directly with explicit SP instruction. SP instruction uses a mix of direct instruction and peer-tutoring aimed at systematically addressing important spelling concepts, word patterns, rules, and expectations [15]

In Practice. Each SP activity simultaneously matches the new LGS and reviews previously taught LGS. SP has three activities based on word structure, letter patterns, and letter sounds (Signal Scramble, Sound Substitution, Justification).

[11] (Swanson, Trainin, Necoechea, & Hammill, 2003)

[12] (Calhoon, et at., 2010; Calhoon & Petscher, 2013; Calhoon et al., in review)

[13] (Carreker, 2005; Templeton, 1992; Templeton & Morris, 1999)

[14] (Adams, 1990; Chall, 1983, Chall & Curtis, 1990; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998; Templeton & Morris, 1999).

[15] (Bear & Templeton, 1998; Carreker, 2005; Templeton, 1983, 1992; Templeton & Morris, 1999).